900presente führte «The Key to Songs» auf

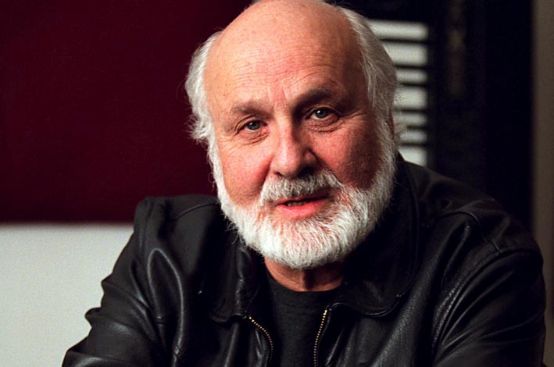

Das am Conservatorio della Svizzera italiana beheimatete Ensemble 900presente führte am 26. März in Lugano und am 27. Mai in Florenz im Rahmen des «Maggio Elettrico» Morton Subotnicks «The Key to Songs» auf. Der Komponist war zu Gast und beantwortete ausführlich einige Fragen zu diesem 1985 entstandenen Werk und zur zeitgenössischen elektronischen Musik (in Englisch).

Where did the inspiration for your piece «The Key to Songs» come from?

That was more than 30 years ago; at that time, from the late ‘70s until the ’80s, ballet companies were doing my music. Every piece I wrote that was recorded was done by ballet companies all over the world. I loved seeing them, and I wanted to write a piece for ballet, but they never commissioned any, because they just took my music after I wrote it and danced to it. So I decided that I would write an imaginary ballet. I got a book by Max Ernst, one of the collage books, Une Semaine de Bonté (1933) and I took pictures from it. It was like photographs of a dancer flying through the air.

It was a surreal book, so there were very strange, surreal poems underneath each of the pictures.

I imagined what the ballet would have been like before and after he was up in the air and I made the music and my own choreography.

One of the pictures in Ernst’s book was called The Key to Songs, and it had nothing but little dots, no words. To me «The Key to Songs» was Schubert. So I picked a fragment by a Schubert song, you hear it, the strings play it often, and it gradually turns into something else. And I used that for the title The Key to Songs.

The funny thing is that once recorded it became a ballet! (smiling). 3 or 4 companies were dancing to that. I eventually wrote 3 imaginary ballets and they got all choreographed!

You worked with Francesco Bossaglia, who conducted «City Songs» concert by 900presente in Lugano at the end of March, for the re-arrangement of your piece «The Key to Songs». How was to work on it again, years later, with a young conductor?

It was really interesting, because over the years that piece got played a lot and recorded. At one point it was my most played piece – ensembles would play it 3-4 times a year and in the last four years, it has been done 3-4 times. It is very interesting that he found mistakes in it (laugh) that I never caught. It is very hard to proof read your own music. When you look at it, you hear what you think is there, you don’t catch the mistakes. I was never very good at proof reading my own music. Since it was played all the time, I never thought that there were any more mistakes. So to find more mistakes at this point is very interesting. I remember pieces of other composers that I had played when I was younger (I was a clarinetist – I played all over) and I found mistakes: for instance in a piece of Schönberg, where there’d be wrong notes, and were published. I thought this is crazy: how can that happen – and now that is happening to me, too. I hadn’t looked at the piece in a long time, and the electronics were different up until fairly recently. Up until fairly recently – even when I first wrote it - you had to play exactly at the tempo that was marked. In the beginning, conductors would have to do it at exactly at the one tempo and no other tempo. In the process of re-doing it we found new technology that allows you to actually change the tempo – not any tempo, but within a range of tempos. That was interesting to find out.

Taking into consideration today’s context about technologies and the fact you are considered one of the pioneers of American electronic music, what is your opinion about current electronic music. Where is it going?

Well, I don’t think anything is going anywhere! I think we’ve reached the point where there is so much information and so many people doing so many different things that we don’t have a direction. I think, rather than a river going in a direction, we have a lake where lots of rocks are falling in all the time, and you have these pools, where it looks like a river, because there are a lot of rivulets but it is not going in any direction. That’s not bad or good, it is just a difference. It used to be that there was an avant-garde and there was the regular music or art and some people were doing things and other people would follow and do it. Now you just find people doing different things.

I’ve talked to young people and they say «Oh, this is old!» talking about something of 5-6 years ago and people are writing about it as if it is old history. Not even a generation: it is only 5-10 years. I don’t see things moving in a direction; each little thing has its own life-form and with electronics when I started at the very beginning – we probably made the first analog synthesizer back in ’63 (I was a clarinetist playing Mozart Concerto with orchestras and touring) – I was very fascinated with the idea that technology at time, which hadn’t really started yet, for music it was going to change everything because it was so cheap.

People in 1950’s could hear music in a concert or maybe on Sunday morning on the radio. But it wasn’t anything like it is now; it meant that only a small percentage of people could hear music.

My first European performance was at the Teatro La Fenice in Venice, during the Biennale in 1963. I was surprised at how small the opera house was – it wasn’t like the opera houses of today: 3.000 people – so music was for a small part of the population of the world. But this was going to be a time with electronics that everybody would be able to hear music from anybody - any kind of music that they wanted. So I decided that I would put away my clarinet and write for musical instruments and electronics and I imagined that 100 years from then that young people who didn’t do like I did (practice four hours a day all their life and write music and that’s all I do all my life), that they would come: they wouldn’t be able to be concert musicians, they wouldn’t be able to be virtuosos, but they would be able to be creative. With new technology they would produce new music.

And I thought that it would be like Berlioz, a new kind of Berlioz, a new kind of this. But what I didn’t imagine that is that they would have not been growing up on Berlioz – they’d be growing up on popular music, so what they did with the technology was an avant-guarde of popular music – not with Berlioz or Beethoven, or whatever. So the direction that electronics have taken has surprised me. They finally caught up with me…

So well I’m doing a premier at Lincoln Center, the promotional material says that I’m the «father of electronica», which is a sort of the … dance music – I never would imagine to be the father of dance music (laughs) or of ballet, even. But I can see why: I used rhythms and things that other people weren’t doing. So that’s the surprise for me. In fine art music I don’t see a major increase in the use of electronics. Where you see the avant-garde that uses electronics, the biggest part of it is in avant-garde popular music. It doesn’t sound popular music any more.

I have been going to festivals – I’ve flown all over the place to perform and to present at these young people. Most of the time I don’t have an audience of people over 30 years old … It makes me feel like the old bear – frozen in an ice age and brought back to life – but that music has changed over the last 15 years. It is beginning to sound more and more like the traditional avant-garde music. Maybe I was right. Maybe in 100 years, not so far from now, there will be a kind of avant-garde that will be a new kind of fine art music. It’s heading in that direction. There is far less dance music now at these festivals – a lot of it is pretty extreme – so maybe that will happen - but that’s where most of the electronics in music is going is to the young people - who won’t stay young, obviously and they will continue to grow, doing some time pretty radical music.

In your opinion, what are the similarities and the differences between electronic music in USA – Europe - Asia?

First of all, when you say electronic music, let’s not call it electronic music: the young people call it electronic music, the fine arts are calling electronic music something else, but rather the «use of electronics». In the area I was talking about just now, where the avant-garde grew out of popular dance music, is almost identical throughout everywhere I’ve been (I’ve been touring Japan and done lots of concerts in Europe).

For instance, I performed in Berlin a couple of years ago in an old movie house where they had just shown a foreign documentary (film) on this subject - on the growth in electronics in popular music. When I walked on the stage at the end, in order to perform after the movie, I noticed I had an audience (it seated about 800 people, and there was standing room only) made up of a wide variety of ages, all grown-up on this new kind of music. It really was a new kind of «fine art situation».

I performed also in Australia and Uzbekistan and I had a big audience. That’s why, I think it is very similar all throughout the world; people are listening to the same music, it’s all popular, that’s what popular means: everybody’s listening to it.

But «Fine art music» is quite different. The fine art use of electronics has come out of places like Tempo Reale in Florence (which I actually helped to set up in the beginning) started by Berio, and IRCAM in Paris started by Boulez. There is a tradition in Europe where that continues. But we don’t have that so much here (US), there is not that much use of electronics in the fine art world. In universities and things, you hear it, but in the general world not so much. Works come out of the younger generation here – for a while they came from Steve Reich. The minimalists affected us much more in the US than they did in Europe. But we don’t have the same traditions: we don’t have a Berlioz, we don’t have a Beethoven, so maybe eventually… I don’t think we ever will. It is too late to get a Stravinsky. Stravinsky was in the US and affected people, but he didn’t come from the US.